So, what actually is AI?

The four key types of AI that are used in industry and how they are used. Large Language Models (LLM)s, Computer Vision, Reinforcement Learning and Predictive Modelling.

If you watch a lot of professional League of Legends you’ll have experienced a sense of déjà vu from time to time. Haven’t I seen this draft before? Chances are, you have. Or at least part of it.

The same few Champions seem to appear time and time again, which for many becomes a source of frustration. It can create a sense of repetition, ruining the excitement of each game as they begin to play out roughly in the same manner match after match.

In this article, I will provide some additional context on how stale it is, I then go on to explain what I believe are the three leading factors as to why teams tend to stick to the meta:

Before we move forward, let’s answer the question: can we measure how stale a meta is?

As of today (5th March 2023), there are 162 Champions to choose from. Each of these could be played in one of the 5 positions (lanes). Thus:

However, there are certain Champions who’s kit makes it almost impossible for them to competitively perform certain tasks. Jungle Jinx, for instance, is unfeasible and certainly not competitive in the highest level of the game.

To give a more realistic number, let’s limit the potential pool to only those played in over 0.5% of high-elo solo queue games this patch1. That leaves us with 225 Lane/Champion viable combinations, or 27.8% of the entire pool.

Note: Not all Champions viable in high-elo solo queue are also viable in esports, so take this number with a pinch of salt - we’ll come back and touch on this point later in the article.

So, how many of these have we seen in professional play in Season 13 so far2

154 Lane/Champions combinations, or 19.0% of the entire pool.

A good portion of these were played once, so, let’s apply the same logic as solo queue and limit it to those played in more than 0.5% of professional games. This takes us to our final number of: 90, or 11.1% Lane/Champions. Almost one-tenth of the entire pool, and 40% of the viable pool.

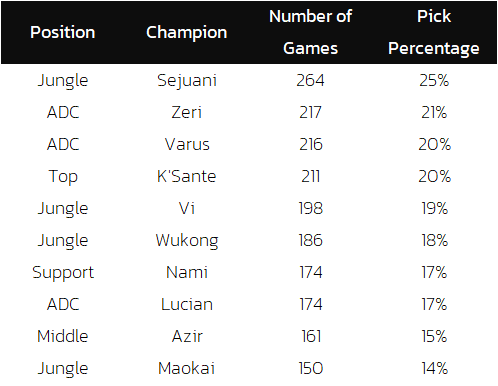

The distribution in the professional scene is also considerably tighter, even when considering the fewer Champions played. The top pick this season, Jungle Sejuani, has been played in 25% of all games. That doesn’t even take into account her presence through bans (as if we did, it rises to 78%). The most popular solo queue Jungler in Patch 13.4 was Lee Sin, but even that barely hits a 10% pick-rate.

Here are the top 10 most played this professional season so far:

Imagine someone built AI capable of playing LoL to the absolute limit. How would it draft? How would the distribution of Champion’s played differ to the meta today?

I can’t actually answer this question as that type of AI doesn’t yet exist for League, however I’d take a guess to say that the distribution of Champions would probably be tighter than what exists today.

In other words, I’d expect for less Champions to be played. Does that mean that actually the professional meta, if anything, needs to play fewer Champions?

This, I can answer: No.

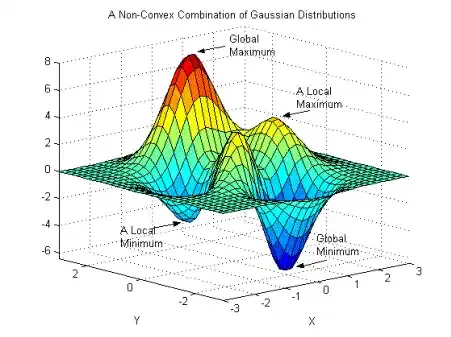

As to why, mathematically we call this the local minima problem.

To visualise it, imagine you have been air-dropped into hilly terrain on a foggy day. You can see only a few meters in either direction. I challenge you to find the lowest part of the terrain. How do you go about it?

Ultimately, there are two answers and which you choose depends on a key restraint: time.

If you had infinite amounts of it, the answer is quite simple. Walk every inch of that terrain, at each point measuring your distance from sea-level and once complete you pick the place where it was the lowest.

However, most problems don’t allow for this unconstrainted “full-search” method. They instead require efficient decision making to do the best possible job in the time given. Often, this means doing a quick sprint around your surroundings, choose the steepest decline and run down it. Repeat until there’s no more declines in your vicinity and then consider that a job well done.

Although inherently faster, you can run into a “local-minima”; an area in which you are the lowest of any visible point within a limited range, but not as low as you could possibly go (which instead is known as the “Global Minimum”).

Look at the graph below, imagine you started at the left most area. You run forward and follow the first decline to the “Local Minimum”. Once there, you may assume you’re as low as you can go, not knowing there’s a much lower point just over the steep hill in-front of you.

By Zachary kaplan - Own work, CC BY-SA 4, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=74756027

A key issue with this, especially when time is of the essence, is that it requires a big push to escape. You are surrounded on all sides by steep climbs without an idea of which direction to head into. On top of this, for all you know you were already at this Global Minimum! Wondering as you climb whether it’s even worth the effort to escape.

This is where the League of Legends meta continuously finds itself. Sejuani Jungle is working relatively well (sort of, her win rate is actually only 47%), as far as anyone knows she is the best option in most situations and the effort to find an alternative is too great.

Ultimately, this all comes down to that one major constraint: time. Or more specifically, effective time. For a team, this can be split into two categories:

Scrims are where two teams play each other in an organised and private practice session. I spoke to one of the Tier 1 coaches about their scrim practice, they had this to say:

“Every week we'll play roughly 3 blocks of scrims, each consisting of 6 games. Of those, at most 2 of them will be effective practice. We're talking 30-40 minutes of interesting game play a day.”

In other words, there’s a very limited amount of opportunity for teams to test and learn, or in our original example; to climb out of the local-minima. Are you as a team really going to use of these 2 effective sessions to test an unknown draft? No, you’ll reinforce what you already know. At a push, you might try something you’ve seen work for other teams in professional play. You certainly won’t be ripping up the drafting recipe and starting from scratch in that limited time.

To exacerbate the problem, in order to perform a reasonable test on a draft you’ll need your players to have a fairly good understanding of how to actually play their Champions. Especially as you’ll be likely competing against teams playing the meta, and thus the opposition players will be comfortable with their respective picks by now. This requires a not insignificant amount of solo-queue time per Champion - only to find out if it could potentially lead to better outcomes, and in most cases will not.

It is this constraint which is a major contributor as to why the meta stagnates so swiftly. To put it simply:

Another point to consider is around the incentive for the game publisher and how that effects the balancing of the game. Riot tends to make their adjustments around the highest level of play, which means there can be large variances in the effectiveness of Champions in your average Silver players solo queue game when compared to professional play. They want to balance for professional play without completely destroying the experience for new or less-skilled players.

For instance, Ryze tends to remain a staple of the professional meta year-after-year, even though he barely gets above a 46% win rate in the depths of low-elo solo queue.

Why is this important? Well, Riot still want him, and similar Champions (Zeri, Azir, Akali, to name a few) to be somewhat played by the average player, and so they don’t absolutely gut them out of viability. This means they tend to skim along in pro play, always sitting somewhere near playable.

The antithesis of this effect are Champions like Master Yi or Nasus who torment players in low-elo but have had little success in professional play. If Riot were to buff them to a point where they could be viable on stage, they would also become unstoppable menaces for the average player.

On top of this, there are certain Champions that can perform well in the highest-elo of solo queue but don’t translate well into the professional scene. For example, Shaco Jungle is a regular across all elos, including Challenger, but due to his almost gimmicky playstyle he is not one for well-coordinated team play.

If you add these two effects together, teams are consistently left with a smaller selection of suitable Champions to play from season to season. As mentioned earlier, players will want to be as comfortable on their Champions as possible - so it makes a lot of sense for them to stick to these regularly appearing characters like Ryze, Azir, Zeri and the likes.

A final factor to consider is the incentive for the coaches to attempt these riskier left-field drafts. Coaching can be a fickle business where job security is measured in months, not years.

Let us imagine you are the Head Coach for a Tier-1 team that has consistently placed 7th, year-after-year. Every season as players come and go, the question looms around “is this the team that finally changes their fortune?”. You are about to play the 1st placed team of your League. The chances of you winning the game is 15%.

If you draft a standard meta team composition and lose, no one expected any different and the general consensus starts to float that these players are once again, not the right fit. If you manage the win, maybe a star player or two is recognised.

However, let’s say you draft entirely off-meta and pick Champions rarely seen in professional play. If you win, you gain some reputation as a genius coach. If you lose, the rhetoric floats around that your team could have stood a chance if they were given a real draft to work with.

The problem is, even if your off-meta draft increases your chances to win from 15% to 30%, you are still losing 70% of the time! That’s 70% “coach is inting the draft” and 30% “genius draft” rhetoric . You are putting your chin out and that always comes with the risk that you get knocked on your ass. You could even finally come 6th, or 5th or even 4th and still there would be that looming doubt that the games you lost were because you weren’t playing the meta and your players are being held back by you.

There is a real incentive to play the meta not because you think it’s the right thing to do, but because it offers the best chance to keep your job at the end of the season (then ask for a new roster that you’ll definitely do better with this time).

If you add up all these effects discussed:

Then you have mostly answered our opening question on what causes the staleness of the meta.

Ultimately, it comes down to the fact that not many teams are capable or willing to risk good in search of greatness.

Here are some other articles that may be of interest.

The four key types of AI that are used in industry and how they are used. Large Language Models (LLM)s, Computer Vision, Reinforcement Learning and Predictive Modelling.

A statistical analysis of how to win draft in League of Legends (LoL) and the AI tool that can do it for you.

Introducing a new cutting-edge AI tool: The iTero AI Coach. Capable of analysing draft, recommending runes, studying your account and much more.